Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:04:11 — 51.6MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

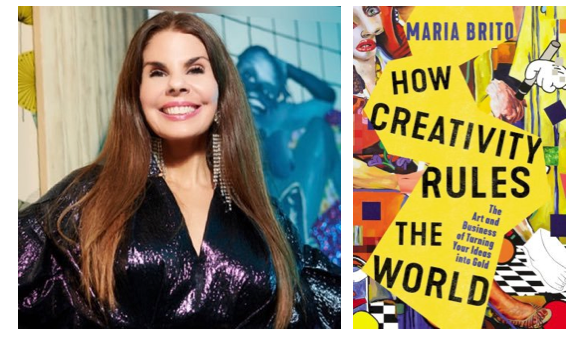

How does curiosity fuel creativity? How can we balance consumption and creation in an ever-busier digital life? How can you break out of the myth of the ‘starving artist'? Maria Brito talks about How Creativity Rules the World.

In the intro, insights into Colleen Hoover's popularity [NY Times]; Amazon bugs [Kindlepreneur]; Ingram invests in Book.io for NFT ebooks and audio [PR News Wire]; The Matter of Everything by Dr Suzie Sheehy; Solid with Tim Berners-Lee [Inrupt]; Microsoft including DALL-E 2 into Designer products [TechCrunch]; Microsoft partnering with Meta for enterprise [Oculus].

This podcast is sponsored by Kobo Writing Life, which helps authors self-publish and reach readers in global markets through the Kobo eco-system. You can also subscribe to the Kobo Writing Life podcast for interviews with successful indie authors.

Maria Brito is an award-winning New York-based contemporary art advisor, entrepreneur, author, and curator. Her latest book is How Creativity Rules the World: The Art and Business of Turning Your Ideas into Gold.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Finding the courage to start a creative business when you have a steady, well-paid job

- How curiosity drives creativity, and how to tap into it

- Balancing consumption and creation

- Why creativity is important for you — and the world

- The complex relationship between money and art

- Embracing technological change in the creative arts — and sharing yourself as the artist in order to connect

You can find Maria Brito at MariaBrito.com and on Twitter @MariaBrito_NY

Header and shareable image generated by Joanna Penn on Midjourney.

Transcript of Interview with Maria Brito

Joanna: Maria Brito is an award-winning New York-based contemporary art advisor, entrepreneur, author, and curator. Her latest book is How Creativity Rules the World: The Art and Business of Turning Your Ideas into Gold. Welcome, Maria.

Maria: Hi, Joanna, and everybody who's listening. I hope you are well, anywhere you are in the world. Thank you for being here.

Joanna: . And we do have listeners all over the world.

Now, I wanted to take a step back. You started out as a corporate attorney at a big law firm. And there are lots of people listening who are in day jobs in the corporate world.

How did you break out of such a high-paying job to start a creative business? How did you find that courage to pivot?

Maria: I think that once you feel the pain of being in a place like that, you can't really think about anything else. But how do I get out of here? And how do I reclaim my life because, literally, I feel that for all the many years that I was doing things that I just did not want to do, it's like I was losing my life.

I was losing my energy and my joy. And when I had my first child, which I was still working at the law firm, I thought to myself that life was short or long, but that I really had a different perspective once I had this child. I have to teach him, by example, how to live a life of joy, and purpose, and meaning.

I had been very, very interested in contemporary art and art history, in general, since I was a child, to be honest with you. And I had taken many courses in high school and in college as well. When I moved to New York City after graduating from law school, collecting informally, things that were young and emerging and fun, and that was always on the back of my mind, how to make people live with art.

When I quit my job and opened my business, that was 2009. The art market and the art world were mysterious and seemed snobbish and impenetrable. I thought to myself, ‘I have been pondering this question for a number of years now, how do people actually get into collecting and living with art and having the excitement of understanding artists through their ideas and their aesthetics without people getting so intimidated, or people feeling that they are being looked down when they stepped into a gallery?

Or how do people demystify the thought that to be a collector, you have to be one of those people who go to Sotheby's and spend $10 million in a painting because the art market and the art world is a whole lot bigger than that?'

So all these preoccupations along with the baby gave me the impetus to say, ‘I don't want to do something that is actually killing me alive.' Basically, because if we talk about mental health today…back then we didn't really have those conversations, but I had them with my husband, and I had them with my friends. And I said, ‘This job is basically is killing me, is annihilating everything.'

Nothing really happens overnight. Because once you have arrived at a place where you say, ‘I do need to quit this job to start something new,' it's because you have been accumulating a lot of painful memories, moments, situations.

It's not just like one day you wake up and you have a big epiphany. It's not like that. It's a long process.

And for people who are listening, if you find yourself hating your day job, know that you're not alone, and know that it takes courage, and it takes time to plan for the big exit.

So if you can do it, because you have been waiting for too long, I can tell you that there is never the right time to do it because you're always going to find whatever reasons.

Our brains are very wired for preservation of safety, and it's difficult for us to actually accept a change of circumstances that is so radical. But again, for me, it was just too painful to stay there.

Joanna: I really resonate with that. I started writing in 2006. Same as you, I was in so much pain, I was crying at work every day. I just hated it. I hated, hated my job.

I know some people listening don't feel that way. They might love their job, or at least tolerate their job, but I have heard from people listening that sometimes their job saps any form of creativity.

I certainly felt like this when I used to implement accounts payable systems.

And I thought, ‘I am not creative. There is nothing creative about me.' And it seems weird now to say that, but I wonder if you could also, you have in the book, there's lots of ideas.

How can people start to tap into their buried creativity?

And if they feel they're not creative enough, or they're struggling with their creativity. What are some of the ways they can find it again?

Maria: Creativity is something from within. I think that I made the point very clear in the book and in my life in general that it really doesn't matter what you do.

Let's say the example or the type of frame you just gave, some people are really happy with what they do, but they don't feel that they are creative.

But the truth is every job and every occupation can benefit from people who can have creative ideas and they can actually materialize them. So, for me, creativity is your unique ability to come up with ideas of value that are relevant. And that actually can happen.

Because a lot of ideas, maybe you don't have the resources, or maybe you don't have the team or the world is not ready yet. How many years Elon Musk has been working on Mars, and he has the resources, and he has everything, and still not happening?

So the point is that creativity is not arts and crafts, and it's not cutouts. It could be, but what it really is, is that ability that you have to come up with amazing ideas. There's no single human being in the world who's not capable of this, bearing some disabilities, of course, but it's the place where people have gotten complacent about moving forward and presenting their ideas.

There is such a high level of stimulus, right around us, that are drowning our senses.

We are consistently consuming social media, and text, and tweets, and WhatsApp, and noise. And people are crossing the streets looking at their phones, and at the same time, they're listening to a podcast.

All these things have taken our ability to think on our feet and to actually be able to pay attention to the things around us that could make great moments to find this idea.

So one of the consensus among the people who are researchers and who are psychologists in the field of creativity is that the number one thing that everyone who is really creative has is curiosity.

You don't need to pay anybody to be curious, and you don't need to be a painter in front of an easel or a writer writing fiction, you don't need to be Stephen King to be curious.

It's people who develop passions outside of their job and inside of their jobs with curiosity are usually creative people, people who are just not happy to get whatever the media says, but they are digging deeply and saying, ‘Is there a contrary opinion to this?'

Or people who have a desire to go with deep research about a topic. And the topic could be anything. Those are usually the type of people who are best with coming up with ideas.

If you feel that you're not creative at work, just find one or two or three things that you feel interested about and learn everything that you can about them.

Or you could even just go and enroll yourself in one of those online courses that you can go at your own pace, and it's a completely different thing that you've never done before.

That's the other thing. Creative people usually are the ones who can absorb information from different disciplines and fields. That doesn't mean they have to be experts. I love the idea of when we look back in history to a guy like da Vinci, for example, who was just like one of the most curious men that we know about, that was written about.

He was ‘I am into writing, and math, and parachutes, and painting, and developing new pigments, and I'm curious about the size of Milan and the perimeter that surrounds Rome. And what can we do to get to France faster?' So this was really a genius.

It's funny because, Leonardo has been dead like 600 years, and we talk about him. And when my kids come and tell me, ‘Mom, do you think that in 200 years, people will be talking about Beyonce or Elon Musk?'

And I said, ‘No, but we are going to be talking about Leonardo da Vinci.' Because that is the legacy of someone who was truly immensely creative. Fortunately, he left us all, almost all of his diaries in his notes are still alive. So that is the beauty of creativity, is that it's all from within. It's motivation.

That's the other thing; no amount of money can make anybody creative. But the motivation that you have from within to claim creativity for yourself and to put yourself in positions where you open up your mind to receive new concepts, to learn new things, to act on different things that you haven't tried before, that is the most magical space ever.

That's why sometimes people are, for example, reading a book, or watching a movie, or watching a documentary and say, ‘Well, though, this does not apply to me, because I am not in the art world, or I'm not a scientist who's looking at the marine soil at the middle of the oceans,' and things like that. And I said, ‘You're wrong.'

Because the place that is most ripe with interesting ideas that you can adapt for you and your career, or your business, or your side gig, or your writing, or whatever, is outside of what you are already an expert.

We are very good at gathering information about our own businesses in our own industries about what's happening, and there's nothing wrong about being a fantastic expert in your field. But what that does also is that progressively, you start developing blind spots because you're so freaking good at what but then everything else that's happening in the world, you're sort of oblivious to. And that is where you find the most incredible ideas.

Joanna: I really enjoyed your book because of that. I like visual art. Most of the rest of the people in my family are visual artists. So I know a lot about visual art and the artists you talk about in the book. I've found it really interesting that way.

You talk more about curiosity and about delving into areas that are not necessarily our area of expertise, but also about noise and too much consumption. And this is a really hard balance.

You only have to look at Twitter or pick up the news, and you feel like we're in the midst of this sort of chaotic time. Especially in America.

When I come to America, I'm ‘I cannot watch your news. It's just so over the top, and it's all crisis, crisis.' And also in the book, you talk about your own difficult personal times.

It's a balance, isn't it, between consumption and creation?

How do we balance this curiosity and needing to consume in the world and learn and be curious, with taking the space to create our own thing?

Maria: I absolutely subscribe to the idea that we need a lot of silence in our lives. And so I have created my life around a lot of routines.

Routines are very, very good for creativity, even if people would say, ‘No, I just want to have crazy experiences each day.'

Sure, you can have that but, make sure that you have a foundation, preferably in the morning, where you start, or maybe you can't necessarily start your day with, meditation and whatnot. But I think that is very important, if you carve out time to just be.

Some people are very concerned about this, meditation and if they have to be sitting down in lotus position with candles and incense and things like that, because usually, our minds tend to go to far extremes in what we need to do or the things that we are avoiding the most are usually the things that we need to do the most.

So while I understand that the speed of life is not necessarily the type of life for everybody who would say, ‘Let me just take 45 minutes every day, 20 in the morning, 20 at night, and 5 in the middle to meditate.' I think that it pays back with interest because it is that moment of calming the mind and allowing yourself to take the focus from everything that is happening around you.

I know a lot of people work in open spaces, are co-working buildings, and things like that. And they are very, very distracting places. I definitely respect because that might be the only option, but I think that anybody has some minutes of the day to practice a form of silence and meditation, perhaps the meditation thing, as I said before, could be a lot of work for certain people, just sitting down with your ideas and contemplation without listening to much or without having to browse through the phone helps because there is a cumulative effect.

If you do it one day and 10 minutes, the next day, 5 minutes, 7 minutes, or whatever, by the end of the week, maybe you have done 45 minutes in silence for the whole week.

Some people practice like a Sunday where, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., they are not going to check the phone, they are not going to turn on the TV, they are just going to try to, perhaps, read a couple of books, or they are just trying to take walks and be present to their families, or if they live alone, then just be doing other things that do not involve all this incredible amount of information.

In some cases, it's really pollution. Like you said, news can be deceiving, over the top, super politicized. If you really need to know something about the news, then you will.

Joanna: Someone will tell you.

Maria: Definitely. I enjoy an excellent written article, long form. Could be ‘New Yorker, or it could be ‘New York Times,' but I don't really enjoy partisan journalism. I know when somebody has an agenda. I'm old enough to know when I'm reading something and there is an entire political agenda behind it.

Listen, I am worried about everything, I'm worried about Ukraine, Iran, China, all the things, but I just can't take them all on me. I sometimes feel that certain people utilize all the things that are happening around them as a distraction, not to do what they are meant to do.

I just have to protect my own energy and space by saying, ‘There is only so much I can do about this thing.'

It's not that I don't care, I very much care, but I also have a family to support and myself and protect my peace of mind and my mental health. I can't partake of every cause. I can't take on every crusade.

This is also an individual responsibility that we have; how much are we going to affect everything that's happening in the world, or can we actually take on a position that is also a creativity space for us that creates the good that we need for ourselves, and that allows us to encore our thoughts and our actions, and the things that we want, rather than all the things that we can't really change?

Joanna: I think what you're saying, just sort of recap there, you talked about meditation. I walk. So I don't sit and meditate, but I walk in nature. And that's where I get my silence. So whatever people do, but you said that protect your space.

You have to protect your physical time to create your mental space from that pollution in order to do the thing you're meant to do. I completely agree with you, that we can use all of this as distraction.

If we're going to create as a lifestyle, as a business even, then we have to make that space.

And the other thing, I guess, what I loved about your book is that it's almost an acknowledgement that creativity and art is important.

And I feel like this is something that happened with COVID. COVID is still around, obviously, a lot of writers I know said, ‘It's pointless to write. There's so many problems in the world. Why am I writing a novel? Why am I writing a story? Why am I writing a book about creativity, or whatever? It's just not important. I should become a doctor and solve these crises.'

How can we center our creativity as important and the thing that we are meant to do with our lives?

Maria: Humans, we are a very strange species. We get this protection from change in our brains. We have physical responses that trigger hormones in our bodies when we are afraid or when we are happy.

I think that the unfortunate thing about the western world is art is intertwined with religion in a way that honestly reads the whole story in, a manipulative way, but it's all about guilt.

There is this sense of ‘I can't really be painting or writing, because look at the world,' and this and that. But actually, the true nature of humans is to progress and to thrive, and to prosper. Without creativity, in every sense, including the arts, we would not have become the civilization that we've made of ourselves.

People would still be in caves, and people would not even have developed language. We have to understand how important language is, the conveyance of ideas, whether that is in a form of a novel, or if it's a non-fiction book, these are the things that keep the world going forward, these are the things that actually, you are always passing the torch on to someone else even if you don't immediately know it.

I feel that there is also a misconception. It's ‘Well, if I am not saving people in Africa with Doctors Without Borders, or if I am not developing vaccines or whatever, then I'm not worth it.'

That's an insecurity also that, unfortunately, has been growing more and more in this day of digital and social media where people tend to compare themselves to others because if they wouldn't have the doctors and they wouldn't have the idea that there was somebody else doing more important job, better things that what they were doing, then they wouldn't have, those thoughts, if that makes sense.

In the era of the Renaissance, these guys didn't have Twitter and people were dying of plagues. No, seriously, it was children would live like to five with luck. And this was the most beautiful and fruitful time in history where the Italian Renaissance in Florence.

We still talk about these guys. We talk about Michelangelo, we talk about Leonardo, we talk about Botticelli. We talk about Dante. These are incredible people. And they were not saying, ‘Because the plague, we're all crying, and let's just hide ourselves in our houses, and cry.' That was not what they were saying or doing.

On the contrary, a lot of them had very strong religious convictions. I believe in God, but a lot of people don't. Michelangelo was ‘I'm serving God with my work.' And he ended up a very rich man, and what he did was, anybody who has seen his work, in person or in pictures, but better in person, has to think that this guy had a power that was just way beyond what a man can do.

Creativity is important because beauty is important, because ideas are important.

Because expression of human beings, whatever means it is, and again, it could be someone who's trading stock, it could be someone who is writing books, it could be someone who's making film, all those things have a purpose.

It doesn't matter if you don't win the Oscar, it doesn't matter if the Pulitzer is not going to be given to you, there is a whole other level of impact with the work that creative people do. And it also is fulfilling for themselves.

I'm sure that you love your podcast because it gives you an expression. And besides all the writing that you've done, this gives you another level of expression that is different, and it's fun, and at the same time, is of service to others.

So all these things have multiple complex layers that are just way deeper than just saying, ‘My job is not important because I'm not saving lives.' Because then if everybody would save lives, then we wouldn't have anybody else to serve us food at restaurants, we wouldn't have farmers.

So imagine, let's say everybody in the world tomorrow saves lives. And so what would happen to all the other occupations? We wouldn't have buildings because people are just saving lives, and we don't have architects, and we don't have people who, construction workers, and things like that. So I get the guilt, but it's not justified.

Joanna: I love that. As you said — it's about fulfillment, it's about human flourishing and creativity for its own sake, which absolutely is wonderful.

Now, I do want to ask you about money because you work with many financially successful artists.

You reference many, both living and dead in the book. I always use Picasso and van Gogh. Picasso died a multimillionaire, his morals were questionable. But many authors, whether they're writers, or visual artists, or whatever, struggle with this art versus money idea.

How do you see the relationship between art and money and/or business?

Maria: I think that the whole myth of the starving artists is romanticized for the wrong reasons. I believe that it's not serving anybody.

Because, as you said, we do have van Gogh who was a bipolar person who killed himself. It's not even the fact that he didn't sell anything, it's the fact that he was crazy. Because, we can utilize that same example today and say, ‘Well, this guy was a genius, but he jumped out of the window before he was able to sell his novel because he was not writing his mind.'

So we always say, ‘Poor van Gogh, he never sold anything.' But then we don't talk about his mental illness. Why is that?

Because people like to romanticize and stay in the pain and say, ‘The art is pure, and the struggle is beautiful.‘

I think those are also mechanisms of defense for people to not do what they have to do, which is do all the work that just goes beyond just making the art.

I have said many times, not everybody is an artist, in the sense of not everybody has the talent to write a novel. Not everybody has the talent to compose a nice painting. Not everybody has the talent to create a wonderful film. This is not to say you're not creative. This is to say that sometimes the idea to do something that you're not 100% equipped is also an excuse for you to say, ‘I'm not making money, that must be because I have to struggle because I chose this particular area.'

Because look, I know doctors who are terrible, and they graduated barely, and they don't make money. I know dentists who are broke. I know architects who live paycheck by paycheck. So the struggle and the starving idea is not exclusive of artists.

It has to do a whole lot more with, ‘Do I have a business mentality, and am I good at what I do?‘ Because I also do know of artists whose work is not necessarily outstanding, but they are such incredible business people. And their greatest asset is their capacity to come up with ideas and to have a team who helps them execute them.

The paradox is that, well, they may not be great artists, but they are great businesspeople. And I think, wholeheartedly believe, that everybody has a very special unique gift and that that gift can be well received in the world. Because, look, honestly, money is loaded as a concept. But money itself is neutral. It's not good or bad, it's not evil or beautiful. It is just that it's a tool.

It's a tool for people to pay their rents, or their mortgages, and feed themselves and their kids and pay for clothes. that's the other thing. If we would have stayed in the system of trade, and barter, and I'll give you peanuts and you give me potatoes, we would not have civilization either. We needed to have a form that actually backed up trade.

So a lot of people are very, very confused about what money means, that, if your art should be just pure and never tainted by money, I don't think any of the guys of the Renaissance was also worried about that. They just saw it as, ‘This is an incredible privilege that I have.' And they had patrons and the Medici paid and they had no problem going there.

That doesn't mean that they were sellouts. No, that means they actually took the help so that they could actually benefit the world with what they did. And some of them were not rich. But regardless of that, they didn't have the handcuffs that we have developed in our culture with money. And that is something that people have to really work.

I know it's not easy. I know, it takes a whole lot of time. There are tons of different tools out there to help you see things differently, to help you see that there are ways. And that if something is commercially successful, that doesn't mean that it is a sellout or that it is bad. That's a whole different story.

Picasso, like you said, was incredibly successfully commercial because people loved his work. But I think the most interesting thing about Picasso is that he worked so consistently throughout his life until the day he died. This man was really…

Joanna: He was prolific.

Maria: But he was invested in that. I can tell you one thing I know for sure, you can never get better if you don't do it over, and over, and over, and over again. You can't really get better at what you do, your craft, the discipline that you put into your writing, or your art. It's a day-in, day-out thing. That is one thing I know.

There are no born geniuses. Well, maybe yes, maybe are people with incredible talent who can, paint, and write music when they are four, or five, or whatever. We've got great examples, and contemporary hits. Justin Bieber was playing that little piano when he was four, and, whatever. So that's fine, but that's only one person. Most people actually put an enormous amount of work in refining what they do.

When you actually put that amount of work and refining what you do with guidance and help, obviously, and feedback, I don't see any negative coming out of that. I see that there's got to be a point where actually is going to pay back.

This conversation could be for days, because there are so many different factors to take into account, but I believe that people's desires, and like what I said before, motivations is what actually gets them forward.

Picasso wanted to paint one and two canvases a day because it made him happy. And he had it within him, he was doing what he wanted to do, and it gave him an enormous amount of satisfaction. It was a very driven-from-within passion.

That is the thing that people should strive always to have, is ‘I feel that I want to do this, and I want to do it more and more because it gives me so much happiness, and I'm good at it, and I'm going to get better because I'm going to do it more.'

Joanna: For sure. Now, one final question because we're almost out of time.

In the book, you talk about questioning the status quo, taking risks, and also that the only constant is change. We're recording this towards the end of 2022, there's this real emergence of AI-assisted art tools like DALL-E, and Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, and a lot of discussion about how that's going to impact the art world as well as the writing tools in the writing world.

How can creatives embrace change and technological progress and still improve their craft?

Maria: Listen, the other day, somebody asked me a very similar question, a friend of mine, and we were having an informal conversation. I told him, ‘Look, a lot of different artists have been using technological tools that are very similar to what DALL-E does and all that for a long time to create renderings, to have inspiration to see what happens when they recompose a figure and an image.'

When people in our history and our contemporary times invest whatever amount in buying a piece of art from an artist, whether that is… And I'm talking about a real piece of art, not an NFT, but I'm talking about something that you hang or you play somewhere.

People are not buying the art alone, they're buying the artist.

They're buying the history, the trials, the tribulations, their backgrounds, where they went to school, how many shows they've had, the things that they talk about, everything, because nothing is hidden anymore.

There was a time where nobody knew who these guys were. They lived in their studios, and there was a wall and there was a shield, and now everything is online, the guys, their resume.

So that part, I don't get too worried about because people buy the artists. Now, with writing, I also take issue with that, because although the writer sometimes can be a little bit more separated off the process…not out of the process, but off the selling part, if that makes sense. You're a great artist, or you're a great writer, the writers are not necessarily having exhibitions every two months. And they are not necessarily in every art fair hanging, and things like that. So it's a different thing.

But the way I see it with writing tools is that there is no computer that can have the experiences that you have had. There is no computer that can actually go through your childhood, your spiritual awakenings, if you had any. The pains of giving birth, the things that you saw the morning that you found your soulmate.

I see it a little bit of a lack of self-esteem for anybody to think that a writing machine is going to be better than them, is going to be better than a creature from the universe who's here, is breathing, is alive is full of soul.

I'm very always invested in this idea that there is spirit, that we are moved because we are alive and there is a soul and there is something inside of us that gives us intuition, inspiration, guides us. So I hope that people who are listening are open to these ideas because that really is what makes us human and who we are, and our feelings and emotions, which no computer can ever replicate.

Joanna: I also think what you said about the visual artists and putting themselves out there, what you're doing, you have a book How Creativity Rules the World and you're here on this podcast, you're being Maria. And I do that with this show. And I have another podcast.

I think by sharing our voices, showing our work and our process, we can put that human artist into the work.

So I think, as with writing, as with visual art, I think writers also are selling the artists and the author behind the creative work as well. So, I love that. Thank you so much. So we're out of time.

Tell people, where can they find you and your book online.

Maria: My website is mariabrito.com. And my book is called How Creativity Rules the World. It is available on Amazon, Book Depository if you'd like to have it delivered anywhere in the world that Amazon does not serve.

If you're in the United States, and you want to benefit the independent bookstores, it's on Bookshop. It's also Barnes & Noble. So there is an incredible host of places where you can find the book. It is in three formats. It's hardcover. It's ebook and audio.

Joanna: Did you read the audio, did you read it?

Maria: I did.

Joanna: Oh, great.

Maria: I did read the audio. But I would always encourage you to get a written version. Because at the end of each chapter, there are exercises that I encourage people to take, ways to digest what they've learned in the chapter, but also, is to get their creative juices going in different directions.

I call them alchemy labs because I think that's where the magic happens, that's where you turn your ideas into gold.

Very little happens if we don't take some action.

So the fact that you're picking up a notebook and up hand and writing things down is one of the ways to create a material record of something that you just learned and you're digesting. That's why writing is so powerful.

I have a whole chapter in the book about writing and about why it is so much better to do this type of exercises with a pen and a paper rather than typing because it really stimulates so much of your neural networks and also your connections between your hand, and your thinking, and paying attention at a specific time, making you very aware of the here and now.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Maria. That was great.

Maria: Thank you, everyone. Thank you, Joanna. I really loved this time with you. I appreciate the invitation. Thank you.

Always helpful to hear a testimonial on someone’s creative journey. Another useful guide is The Artist Way by Julia Cameron (no relation). She takes a deep dive into discovering the path of creativity. My copy is “dog eared” from use. Thanks for your continued podcasts – always helpful.