Podcast: Download (Duration: 57:26 — 46.8MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

You are not writing one book. You are creating an intellectual property asset that can make you money for the rest of your life and 50-70 years after you die.

In this interview, David Farland talks about the importance of valuing your writing, and how to keep a long-term mindset as an author.

In the intro, Jeff Bezos steps down as Amazon CEO [WIRED] and what that might mean for the focus going forward [VentureBeat]; Bill introduced this week to reform antitrust law and retool regulatory agencies to confront anticompetitive behavior by big corporations—notably, tech companies [Fast Company]; Prolific writing on the 6-Figure Author Podcast; and How to Market a Book: Overperform in a crowded market from Reedsy CEO, Ricardo Fayet.

Plus, Microsoft has launched Custom Neural Voice in limited preview, a service that allows customers to create custom voices with AI [VentureBeat]; and I discuss the current state of writing and artificial intelligence on the Ask ALLi show.

This podcast is sponsored by Kobo Writing Life, which helps authors self-publish and reach readers in global markets through the Kobo eco-system. You can also subscribe to the Kobo Writing Life podcast for interviews with successful indie authors.

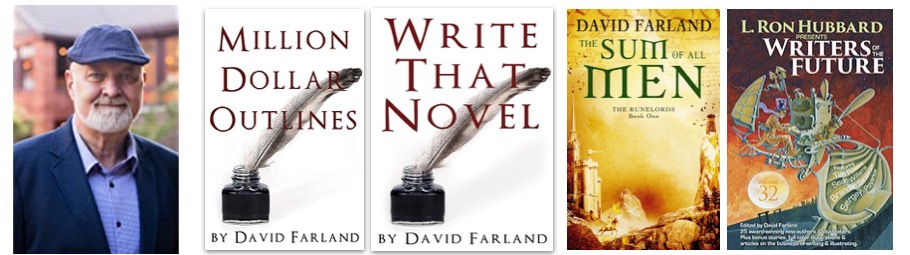

David Farland is the multi-award-winning and international best-selling author of over 50 novels and anthologies across science fiction, fantasy, and historical fiction. His nonfiction books for writers include a Million Dollar Outlines and Drawing on the Power of Resonance in Writing. And he offers courses and online community and workshops at MyStoryDoctor.com.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and full transcript below.

Show Notes

- How the pandemic has affected publishing and how business models might change moving forward

- Why some contract clauses might be a deal-breaker

- Thinking long-term about your intellectual property

- The different types of audiences that are important for a book

- Constructing a story arc that might work for a TV series

You can find David Farland at MyStoryDoctor.com and on Twitter @davidfarland. You can also get his Super Writers Bundle of books and courses, on sale now.

Transcript of Interview with David Farland

Joanna: David Farland is the multi-award-winning and international best-selling author of over 50 novels and anthologies across science fiction, fantasy, and historical fiction. His nonfiction books for writers include a Million Dollar Outlines and Drawing on the Power of Resonance in Writing. And he offers courses and online community and workshops at mystorydoctor.com. Welcome back to the show, David.

David: Thank you. It's great to be here.

Joanna: It's been a while since you were on and you've obviously been writing and publishing since the late 1980s.

What your thoughts are on the current state of publishing, especially since the pandemic seems to have driven so much online?

David: It's interesting because we've had two publishing worlds for the last decade. We've had traditional publishing. And yet we've had this huge boom in indie publishing. About 55% of the money paid to authors up a year ago was actually paid out to authors who were indie publishing. That's turned into a really good market.

But this year, with the closure of so many bookstores and the COVID regulations, we've seen about an 18% increase in the number of sales in the indie market. It's creating even a bigger boom in that market. The indie market is going great, the traditional market is on rough times. A lot of the publishers have been closed, and a lot of the book printers have even been closed. You can't even get the books printed.

So I think that's changing. Things are warming up. But it's been a long, tough year for the traditional markets.

Joanna: Those publishers who have eBooks, digital, audio, and print on-demand have been able to surf these changes. But what do you think will change for traditionally published authors?

What will traditional publishers do now? Are they going to change their business model to be more like indies?

David: I think so. The truth is that for the past 10 years traditional publishers have been kind of demanding more rights from authors. So the advances have gotten smaller. I've heard people say that $30,000 is the new $100,000 advance, and yet at the same time, they're taking a large amount of the money that comes in from the digital rights.

If you're selling as an indie author on Amazon, you can earn up to 70% of the money that's paid. Whereas with traditional publishers, you're usually only getting 15% of the sale.

So you're taking a mighty big hit. A lot of that money is going to the traditional publishers, and that's how they're staying afloat. I think that what's going to happen is that traditional publishers will keep demanding more and more rights.

They'll ask for more from authors. And by doing that, they make it a less attractive proposition until authors start to realize, ‘Gosh, I can make more money this way.'

I was just talking to an indie author who went traditional and has been doing quite well. But he makes half a million dollars on a book, and in traditional publishing, he's only getting about $150,000 out of that. So he decided that, yes, he's going to go ahead and go back indie again.

That's the method that he's using. I don't know that I want to mention his name but he's one of our big authors that's in the indie market and has made that transition.

I see it almost as a bridge where people start out as indie. They make it good. They get traditional publishing deals that broaden their appeal, broadens their name recognition. And then suddenly, they can find themselves back in the indie market.

But as an indie marketer, he's using Kickstarters to go out and get his books published so that he has books that are in print, that are in the major bookstores and stuff around the country. So that's a really good model for him.

Joanna: It is interesting because I was researching more on Kickstarter. I feel like Kickstarter has been around for, I don't know, maybe a decade now. At least eight years. Something like that. You and I have both have been in the publishing industry that long.

I feel like when it arrived, I thought, ‘I'll never do that because I don't like that idea of asking for money upfront. I don't want to do that kind of thing.' Because what the projects that were done on Kickstarter at the beginning seemed to be quite different to the ones that people do now.

I was looking again the other day, and I was like, ‘Wow, you can really do some interesting things with Kickstarter now.'

Have you been looking at Kickstarter, too? Because, obviously, you have a really big audience.

David: Yeah. I'm just doing a Kickstarter now. It's not really me doing it. There's a little tabletop game company that's doing a game based on ‘The Runelords.' I'll send you the link because I don't remember the link exactly, but it's Red Djinn is doing it.

They're doing a tabletop game and they're looking for $50,000. We're over halfway there after a week. The point being, though, that this is a great way to build an audience while you are trying to earn money for your project. You find people who like to do it and if you do it really well, you can make a lot of money.

One of my students, Brandon Sanderson, ran a Kickstarter a couple of months ago and made $6.7 million to do a collector's edition of one of his books. And it was like 10th year anniversary of the book so it's not even a new release. This is just a collector's edition.

But he's done a number of Kickstarters. I think he's done about 10 or 12 of them. And so he's built up a huge audience on Kickstarter. And that's a great way to go. It really added to his audience.

I don't think that Brandon has ever had a $7 million contract for one of his novels yet. I don't know that for sure. But that's a huge amount of money for an author. That's enough to live on for the rest of your life just off of one book.

Joanna: I've been using his example quite a lot recently, because it was a special edition reprint of an old book. That's what's so brilliant. It wasn't even a new book.

But, as you say, publishers seem to be taking a lot of rights.

Someone forwarded me a contract recently where it said, ‘All formats existing now and to be invented.'

And I was like, ‘I'm sorry, that is ridiculous.' And someone like Brandon, who's obviously very savvy, kept special edition and managed to make that much money from it.

But you, obviously, have a lot of students. You see a lot of things going on in the publishing industry. This ‘all formats now and to be invented,' Is that a contract term that people should consider or negotiate?

David: I think it's a deal killer because if you look at Brandon, I've tried to do this with my publisher to see about doing special editions. And they just said, ‘No.' Even if I pay them money and pay them a royalty on each one, they wouldn't do it.

What you have is your publisher acting as kind of a bottleneck. We were driving to do a book signing together when Brandon came up with the idea. He mentioned that he wanted to do these collector's editions someday and thought it was a really good idea. And this was like in, I'm going to say 2007 or 2008, something like that. And so he went and carved out the rights on his next contract. So I think you have to do that. You have to be planning ahead for these kinds of things.

Joanna: I agree. And so with your students now, you mentioned maybe going indie to trad, back to indie. And there's sort of people doing hybrid like Brandon, doing a bit of both.

Is that the best career now, is keeping options open, doing a bit of both?

David: Yeah. It's called a hybrid author, and there's a recent survey that I saw. And once again, I'm going to tell you I can't remember where I saw that. What they did was they did a survey of about 1,000 different authors, and some were traditional and some were authors who were indie only.

They found that the authors who were hybrid authors who stepped into both worlds made about 30% more money. Now, that might not seem like a lot of money. But if you're making $100,000 a year, $30,000 becomes a pretty good safety cushion if you're making an extra $30,000 a year.

I'm of the opinion that you never know where your next meal is coming from as an author. You don't know if you're going to get a big deal. I have one author that I know who quit writing because her books weren't making any money. And then she became a number one bestseller in Poland and made millions of dollars in a very small country.

As a writer, you just never know when you're going to get a deal like that. And so you have to try to keep your options open.

Joanna: As you've talked about in Million Dollar Outlines, you actually talk about intellectual property and how your ‘Runelords' series, which you just mentioned with that tabletop game as another example, you said it's made you multiple seven figures in terms of income over its lifetime so far.

Explain what are some of the other forms of income that you've made from ‘Runelords?'

If people don't really get it, could you explain how that intellectual property works?

David: When you're writing a book, I want you to think of it not as a book. Most people are hobbyists and they think of a book and they hope that they're going to be able to sell it to their local publisher.

I know people who make the mistake of going and, let's say they're writing in Australia and they were like, ‘I'm going to go to my small local publisher because I know the lady down the street, and I'm hoping that she'll take my book.' And that's their goal is to sell to the lady down the street.

But when you're a writer, what you are is you're an international business person. You are creating books and you should sell them all around the world.

And so your goal isn't to sell it down the street. It's to sell it down every street.

There are authors that I know, for example Dan Wells, one of my students that was with Brandon Sanderson in his 318R class years ago, he went out and his first book sold okay. He got a nice little deal in the U.S.

But then his agent took it and got a huge deal in Germany. And then that led to a big deal in France and another fantastic deal in England. He was selling his books all around the world and had to quit his day job just after about two months just so that he could keep up with his writing career. He made hundreds of thousands of dollars by doing that.

We're always looking to, first of all, foreign rights. But then we look to other things. For example, this tabletop game. I've got a meeting on Sunday to talk with the guy about a video game for ‘The Runelords'. I've got three movie companies right now who are looking at doing ‘The Runelords' as a TV series. And then you've got the possibility, of course, of doing audio books and electronic books, and on and on and on.

So when you sell a property like this, you don't know where it might break out. When I got a sale to Japan, for example, my advance that came in was for, I think it was $100,000 check, from a little country that I've expected a couple thousand from. I had no idea. So that made a nice Christmas gift just the day before Christmas.

You just never know where it's going to break out. And you never know when it's going to break out.

I've known authors who write a book, like I told you about, my friend who quit writing in the United States and her book went on to make millions of dollars in Romania.

But then 15 years, or it was about maybe 15 years later that it was published here in the U.S. again, in hardcover, and made millions of dollars again.

It's sort of like when you create a property, you don't know where it's going to take off or when it's going to take off, but you have to prepare the ground so that it can take off.

If you have a little deal, a little contract that limits you and says, ‘We're going to publish in all rights and all formats and hold these rights forever,' you've just given it away and you don't know how well that publisher is going to promote your work or if they're going to be able to do it properly. You're taking a huge risk. That's why I say a deal like that for me, it would be a deal killer.

Joanna: Having this long-term view is so important. I feel like that's maybe one of the problems that the indie community has, because it's so focused on algorithms and immediate sales and immediate income.

I also think there's a bit of perhaps under-confidence about indie books that still remains even though things have changed since the days when it was a stigma to self-publish.

How can we keep that mindset of long term and be a bit more confident in preparing the ground, as you say, in case it does take off?

David: I think you're absolutely right. With indie publishers, they often talk about trying to appeal to what they call ‘the whales,' the people that are super readers who make up about 92% of the audience for a new book.

The problem is that there are multiple audiences for a book. There are people who read habitually, that read five books a week or something like that. And we can appeal to them, but there's not very many of them.

What you want to do is move beyond that book. I say that there's another audience behind that book and that's the audience that I call the true believers. They're the ones who look at the reviews and they look at the awards, and they'd go out and they try to find the best books they can based upon that.

As an indie author, I don't think you should just appeal to the whales. You should also be trying to appeal to that second audience.

And then there's a third audience after that. And that third audience is what I call the bandwagon jumpers. Whenever there's a bandwagon that comes by, they want to jump on it. For example, years ago I was asked to help promote a book big, and I pushed the book ‘Harry Potter' at Scholastic.

Joanna: Oh. Never heard of it!

David: ‘That's the one you ought to push big.' And, at the time, that was a pretty audacious move. There had never been a number one ‘New York Times' best-selling middle grade book. And so that was kind of strange.

But beyond that, when we did that, there was a market that was estimated to be about four million people for middle-grade books. And we wanted to sell eight million copies. That's what I figured they needed to do to be profitable.

They went out and promoted that book and it sold 500 million copies to date worldwide just for the first book in the series. It's made billions of dollars for the author because I figured it out now, and Rowling ought to be up at around the two-billion-mark instead of the one-billion-mark that she became famous for passing.

But the point of all that is, is the bandwagon jumpers are the ones that you want to get to. And you've got to pass through the true believers to get to that huge, vast audience that's sitting out there beyond that. As an indie author, I think you need to think bigger and explore your options.

Joanna: I agree. And as you mentioned there, you've picked books in the past. And you've also been a judge for lots of things, including the ‘Writers of the Future.' You've coached best-selling authors like Brandon Sanderson, Stephenie Meyer with Twilight, obviously, some real books that stand out.

How do we try to write? We have to write what we love in terms of genre.

What makes a book stand out from the pack when it comes to awards?

David: I think there's so many elements. I happen to be lucky in that I have what I would call very mundane tastes. I like the books that everybody else likes.

When I was a kid, I used to listen to songs on the radio with a couple of friends and we would guess on how high they would hit on the bestseller list and how soon they would hit. I could pick them just about every time. I don't know why that is, but I think I learned to gauge what public tastes are.

People want stories that move them emotionally. They want stories that are beautifully written.

They want stories that they've never seen before that feel original, that take them to new places. There are so many different elements that I can't just talk about one.

That's why I had to write a book like Million Dollar Outlines where I talked about a number of different things and also talked about, ‘Okay, beyond writing a book, you've also got to figure out how to sell it.' And so it has to be a book that's not just about writing, but about marketing the book.

So that was kind of a different approach that I took to this. This is something that you can study and you keep finding insights the more and more you look at it. I've been doing it now for over 30 years, and I'm still learning.

Joanna: It's one of those annoying things, obviously, as a writer you kind of want to write something that can become so extraordinary, but it's difficult.

You've written so many books, and it seems like your ‘Runelords' series is the one that has been the biggest in terms of intellectual property returns, I guess. You can't hit it on every book, so do you just have to hope for once in a lifetime?

David: It's kind of funny, but when you study authors, you can almost always find one big book that did it for them. And so you'll find a writer like, let's go with Frank Herbert. Dune is the best-selling science fiction novel of all time. But he wrote a bunch of other books that were pretty darn good. It wasn't like he came out of nowhere, but nothing that he ever did before or after had received that kind of acclaim.

Let's take another author, Orson Scott Card. His big book is Ender's Game. He's written a couple of books that I like better than Ender's Game. I think Ender's Game is a wonderful book and I'm happy to recommend it. And I tell kids, ‘Yeah, you go read this book.'

But there's a couple of other ones that he's done that I like just as well or better. But somehow, they didn't get the promotion that the publishers needed to put out there, or it came out at maybe the wrong time, or people just didn't quite understand it because it was written for a slightly different audience.

You can look at something like Speaker for the Dead that he wrote, which is a wonderful book, and, in my opinion, I liked it even better. But I think that it's for a different audience group. Ender's Game was for preteens or teens, I should say, and preteens.

Speaker for the Dead is for a more mature audience, the kind of people who have to deal with death and dying. And you can look at something that he wrote like Lost Boys, once again a wonderful novel, but it's going to be more powerful for young parents to read. And so it's, once again, a different audience. And it just didn't get the popularity that Ender's Game did.

Joanna: Is the secret then just to keep writing?

David: I think that that's a big part of the secret.

A writer should always keep writing, always be joyful in what you're writing about.

In other words, pick the things that you love to write. Ignore editors. Editors have been wrong so often that you should just ignore them as an entire species.

What I mean by that is if you look at the best-selling books of all time, okay, when I chose Harry Potter and told Scholastic to push it big, the first remark that the managing editor made was, ‘That book was rejected by the 12 biggest publishers in the world.'

I said, ‘I hadn't thought about that. But, yeah, that makes sense because you're not the biggest publisher in the world.' And I said, ‘But editors make mistakes.' And she said, ‘I agree.' So we talked about how to push Harry Potter.

But you look at other books, okay, if you look at, for example, the best-selling science fiction novel of all time was Dune that we mentioned a few minutes ago, it went to 42 different publishers and was published by a group of people that were selling books on how to fix engines. So they would have a diagram of an engine and tell you what screw you needed to put in your engine to fix it.

Or we had the case of A Tale of Two Cities. Never did find a publisher. It went to every major publisher in the United States and England and didn't find a home. It was self-published and became the best-selling book of the next 150 years.

And we can do that again with Gone with the Wind, the best-selling romance novel of all time which went to 27 different publishers and was rejected. It's just so often that happens that I look at it and I go, ‘If a publisher rejects your manuscript, send it to another one.' That doesn't necessarily mean that the editors were right. So often they're wrong. Just go ahead and keep pursuing it.

Joanna: And then, of course, there's indie authors, a lot of people choosing to self-publish first. You mentioned the film and TV adaptation for Runelords, and a recent example is Bridgerton, which is based on books, and The Queen's Gambit, some of the biggest things on Netflix in the last year.

Do you think that as indie writers it's going to be harder to get into that kind of adaptation, considering that it's the literary agencies that have a way into media?

How do you best think we can position our books for the screen?

David: I think that what Hollywood is looking for, quite frankly, it's interesting that very often they're looking for something that nobody else has seen. They're looking for a good story about your book. So if you've got a book that you've written and let's say you put it up for some awards and it wins a couple of big indie awards, that is going to interest the folks in Hollywood.

If you have good sales numbers, that's going to interest them. But, ultimately, they're looking at a story.

Now, when they're trying to create a big TV series, the TV series, they may want to run it for 12 or 15 seasons. And so most of the time, if you've got a novel, you probably don't have 15 volumes that you can do over 15 seasons. And sometimes when you do a season, it's only two or three books. If you did 15 seasons, you're talking 45 novels.

It's hard to have a story that you sell. What they like in Hollywood are interesting characters that you can sell. In other words, something like one here in the U.S. called ‘House' that you've probably seen about a doctor who's brilliant but kind of a nasty person. And that one, you know, went on for several years.

And we can look at stories like The Queen's Gambit where we've got a fascinating character. That kind of thing can go on for years.

Joanna: With The Queen's Gambit I think the author is, terrible to say, I think he's dead.

David: That's too bad for him because he could be enjoying his success.

Joanna: But that's what's interesting is, as you say, you never know when that might be a success. And, of course, there are heirs and successors in the future, but copyright does go on after the death of the author. So that's even interesting as well.

Do you think storytelling has changed due to the popularity of binge consumption and gaming as well, which offer these longer, immersive stories?

David: Absolutely. I work with a number of movie producers and things like that. And the producer that I'm working with right now who took ‘The Runelords' out, we have three studios who are taking meetings together trying to figure out whether they want to do a big TV series or whether they want to do a movie series or nothing at all. It's Hollywood, you never know what they're going to do.

One of the things that I keep looking at is, for example, they're saying, ‘We'd like to see another proposal for another series.' I'm working on that right now this week. And they're saying, ‘We want to see what the story arcs would be for the first eight years.'

That is like plotting an eight-novel series. And that's a big major job right there. And that's what I'm hearing from everybody right now. ‘We want to see a big arc that takes us through the first 8, 10, maybe 15 seasons.'

I just did one where they asked to see a dozen seasons and just get a general idea of what was going to happen, which is a huge waste for the author because then they're going to have Hollywood writers go in and actually write the thing and it's all going to change anyway. So it's sort of like wasted work, except that maybe they'll fall in love with some of the ideas and use some of them.

Joanna: I'm fascinated. Personally, how are you doing that? What's your creative process for story arcs?

How do you come up with story arcs that are so big?

David: My creative process is I like to develop the world first. Because I think your characters have to grow out of the world that they live in. And so with a big fantasy like ‘The Runelords,' that meant sitting down and creating a map of the world and then dividing it into nations, and then creating a history of each nation and some ideas about who ran it and what their imports and exports were and what kinds of creatures lived there, what races lived there, those kinds of questions.

After I created the world, then the characters have to grow out of that. When we're dealing with an epic novel, a fantasy or a science fiction, that usually means it's a story about how one way of life crumbles, one civilization collapses, and a new one begins. That's what epics are.

If you look at something like Lord of the Rings this is how the story of the collapse of Sauron and how a new age began.

So what we do is you start thinking about it in that term. And usually, it's not just one person who brings about the collapse of a civilization. That's beyond the power of any one person. It's usually a collection of people. And some of them are going to be powerful and important people like Gandalf and Aragorn and that type of thing. Other people are going to be ignoble. They're going to be the invisible warriors, the little Frodos who make a major contribution and yet nobody knows their names.

What I do is then I look at it and I say, ‘Okay, how do I weave these stories together?' Let's say that I've got half a dozen major protagonists. How do I tell their story in such a way that I can captivate an audience and always keep them fascinated? What revelations are going to come out? What side problems are going to need to be dealt with? What love interests are they going to have? What deep mysteries are going to be resolved?

It's just a matter of basically spinning a big, fantastic yarn.

You're taking each of these story threads, and you're weaving them together into a fabric that people see and that becomes wonderful.

Joanna: I've been watching a lot of Netflix, obviously, during the pandemic. And we've watched a few series, which is sort of YA fantasy with the group of people and the one discovers their power and all of that. You talk about this I think in Drawing on the Power of Resonance in Writing, that it has to be something that we've seen before, but then it has to have an edge of difference. What you just talked about there as epic fantasy, we've seen those stories before.

I feel like that's the thing that perhaps is a struggle, to know where's the line between giving a story that people want to see the same sort of structure, and then something that's more original. What makes it different?

David: Absolutely. I like to put it this way. When we start writing a story, we start telling a story about somebody else. We talk about Frodo or Gandalf or something like that.

But by the end of the story, the reader should realize that the story is about them.

I'm not writing a story about another character, I'm writing about you. And the things that Frodo learns are things that are important for you. The struggles that he goes through, you go through metaphorically. You're living through them in your imagination. And so you're going through them, too. By the end of the story, you should be Frodo and Frodo is you.

That's what we're trying to do. And I think that, too often, the big problem in Hollywood is that Hollywood writers just don't get that. They write stories about people that they think might be cool and interesting, but they're off at a distance. They're not bringing them into the heart of the readers. And so that's the big weakness.

Joanna: I could ask you questions forever, but we're almost out of time.

Tell people what they can find at MyStoryDoctor.com and how do you help writers there?

David: I help writers a number of ways and, as you've mentioned, I'm the lead judge for the ‘Writers of the Future.' You can find out about ‘Writers of the Future' at www.writersofthefuture.com. And that gives you the rules. That's one of the largest writing contests in the world. If you write science fiction and fantasy short stories, I'd love to see those. And that's a huge thing that I do.

At mystorydoctor.com, you can find links to my books on writing. And you can find links to my courses on writing. I have two things that are going big right now. One of them is I teach the Apex Writers Group, and that's a group for writers.

We're all locked in with COVID right now and so we're not meeting in writing groups. And that's become really popular, have writing groups online. So I bring in major guests. I bring in editors and agents and movie producers and things like that. And we talk about writing each week.

I also put my writing courses online so that you could take those in conjunction with other writers. You can meet together in productivity groups. We have a lot of people who write together each day, and they have like writing sprints each day, that kind of thing. So they're really helping each other, push each other's work along. And so that's one of the major things.

And then the other thing is just getting to the writing courses. I've got a nice sale on writing courses. I've got my Super Writers' Bundle where I've taken all of my courses, and you can take them. You won't get comments from me, but you can take the courses and then you do them together with other people in your writing groups or writing friends. And it makes it very, very affordable to do it that way.

It's $200 for all of my courses together, which is about 90% savings over what they would normally be if you took them under my direction. So those are the kinds of things that I have there.

Joanna: Brilliant. I've read all of your nonfiction books. In fact, many times. I've read Million Dollar Outlines over and over again. I really appreciate your expertise. Thanks so much for your time, David. That was great.

David: Well, thank you so much, and you have a wonderful day.

Best, most useful and inspiring interview yet!

Thanks for the shout out and link to our podcast, Joanna!

I always listen, Lindsay 🙂