Podcast: Download (Duration: 50:53 — 41.5MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

Many authors have a goal of seeing their book made into a film or TV series, but how can you maximize the chances of that happening? Ken Atchity has some tips for creating loglines and standing out in a crowded content market in today's show.

In my personal update, Productivity for Authors is now available in all formats, and I am almost finished the draft of Audio for Authors: Audiobooks, Podcasting, and Voice Technologies. I talk about the impact of Google BERT on search and how it might impact you if you do content marketing, as well as some thoughts on spring cleaning in your author business. If you have an older website like me, check out SEO 2020. Plus, the Writer's Ink podcast with J. Thorn and JD Barker.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, where you can get free ebook formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Get your free Author Marketing Guide at www.draft2digital.com/penn

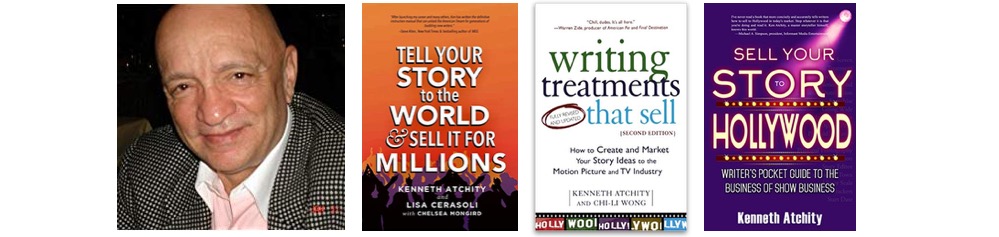

Dr. Ken Atchity is an author, producer, literary manager, and editor. He and his story merchant companies have written and developed books, screenplays, and films for television and cinema. His books for authors include Tell Your Story to the World and Sell it for Millions. And his films include the action, adventure, thriller, The Meg, which I personally loved.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript below.

Show Notes

- How Ken went from academia to Hollywood

- What the journey looks like for a book that becomes a film

- Why it’s a good time for storytellers in Hollywood

- Tips on writing a treatment

- Why a clear premise sells a story

- Why character matters when finding a story’s premise

- Why it helps to have a representative in Hollywood

- Should you think about the budget when writing for the screen?

You can find Ken Atchity at StoryMerchant.com and on Twitter @kennja

Transcript of Interview with Ken Atchity

Joanna Penn: Dr. Ken Atchity is an author, producer, literary manager, and editor. He and his story merchant companies have written and developed books, screenplays, and films for television and cinema. His books for authors include Tell Your Story to the World and Sell it for Millions. And his films include the action, adventure, thriller, The Meg, which I personally loved.

Welcome to the show. Ken.

Ken Atchity: Well, thank you so much. Thanks for having me. It's a pleasure to be with you.

Joanna Penn: This is very cool.

Tell us about you and your writing background and how you got into film and TV because you have a bit more of a classical background.

Ken Atchity: I was a professor for years before I went into film and TV and I taught, among other things, medieval English, and therefore knew all about Bath, the wife of Bath’s tale and a Chaucer and so on. But I was primarily focused on Latin, Greek, and the Renaissance. Totally different from what I do now, although I'm developing several TV series in some of those areas.

One on Sappho and one on the Roman empress Theodora but that was completely different background, comparative literature, Yale PhD. And then one day I decided that I wanted to be on the other side of storytelling instead of analyzing and reviewing stories.

I refined my work developing stories with students and my own stories and finally made the transition to being a literary manager to a producer.

Joanna Penn: It's interesting because you make it sound so simple that like to go from academia to Hollywood. Whereas in my mind, and I'm sure many people listening, those are two very, very different worlds.

How did you have to change your entire mindset and the way you worked as well?

Ken Atchity: That is a longer question than the way I answered it.

I actually wrote a book about it called Quit Your Day Job and Live the Life of Your Dreams because I was a tenured professor. My reaction to getting tenure after, I think 10 years in academia was depression because I really hadn't thought about what I was doing as being in a golden cage of security and security has never been my primary value.

My primary value has always been creativity and freedom. And of course, security and freedom are both illusions, but freedom was my preferred illusion where security was my father's preferred illusion. And, I just decided I needed to have a more daring life and went into the world of commercial storytelling.

They say the academic world is the world of ideas. And to some extent, that's certainly true, but there's nothing like the world of ideas to compare with Hollywood. In Hollywood we track ideas. We trap ideas. We buy and sell ideas for millions of dollars, and we hope to lure audiences all over the world through screens just to see these ideas turned into stories and movies. So it was quite an evolution.

But it all began when I came up with an idea that ended up being 16 films, and that was my first project. It was called the Shades of Love project, and it was love stories that I ended up shooting in Montreal and was producing in Toronto and were distributed all over the world by Warner and by HBO, Cinemax.

I certainly had the bug by that time and continued in this world, where I find stories, develop stories, and then sell stories, produce stories, and market them afterwards to make sure they try to get to the screens they should be in.

The Meg being the biggest example because we brought in $560 million worldwide so far, and hopefully we'll be doing the sequel next year and was quite exciting.

Joanna Penn: Let’s talk about The Meg because when you emailed me and you mentioned it, I was like, yeah, I love that movie and my regular listeners will know I'm such a fan of action adventure movies. I'm also a fan of Jason Statham, so I'm the perfect target market for that film.

But then I looked more into it and it looks like the Steve Alton book was published 20 years ago? More than 20 years ago.

Many listeners would love a film and TV deal.

What is the journey from a book like that to film, given that it's been so long?

Ken Atchity: Well, the journey looked like it was going to be real fast because I virtually sold the film rights within a couple of months of selling the book rights, and as I sold them to Disney.

And Disney, the way big studios do, had it in what we call ‘development hell’ for three years, which is nothing. Then it went into what's called turnaround, where the studio loses the rights to it because they haven't produced it yet. And then it's a few years later, I sold it again for over a million dollars to another studio that took three years before they released it. And then years went by and then it was finally sold to Warner brothers.

By then, Warner Brothers owned the second studio that I had sold it to, New Line and it went into development at Warner Brothers for years until finally it all came together.

By the time it hit the screen, it was 22 years after the first sale. And that's at the other end of the bell jar curve because I've had movies move into production as quickly as three to four months. A movie called Joe Somebody with Tim Allen, but The Meg was, as far as I'm concerned, is the longest it’s taken any movie that I've been involved with.

Joanna Penn: I've actually spoken to a few writers recently and it has taken 20 years. So they're thinking this 20 years thing is a big deal, but it's good to hear things can move more quickly.

Most authors would, including myself, obviously, would love a film and TV deal and we have lots of ideas. Most of us own our own IP on this show. Many of us are independent authors. And I notice that Steve Altern has a literary agent, traditional publishing.

How have things change now for independent authors and creators in this market?

Ken Atchity: They've only changed for the better, in my opinion.

There are pros and cons, but the biggest pro is that there are more channels and outlets for stories than ever before. And the good news is that the strongest of those are now television, whereas 20 years ago, the strongest by far was film.

Now everybody in film is trying to get into television, whereas before people in television were trying to get into film and weren't exactly welcomed. The snobbery has reversed now, and TV is much more powerful because there are so many channels, that they're all competing for programming.

And of course, it's now going to another dimension with Amazon and Netflix becoming studios on their own and producing their own stories. So it's never been a better time for storytellers as far as placing stories.

And the good news is they are likely to get more of the back end of a story than they ever would have in the past. But the bad news that they don't get paid as much up front as they used to because there's so many channels and because everybody is much more frugal in today's world than they were 20 years ago.

It couldn't be a better time for storytellers. We're always looking at my company, for example, for series, because that's the home run, is to have a series of books that we can turn into a television series and sell to a major outlet like stars or Netflix or Amazon or Hulu, or Apple or Lifetime or any of the others that are out there.

So I think it's a very exciting time for storytellers.

Joanna Penn: Having done a little bit of looking at this myself, pitching a TV series is very different to pitching a film.

If people are submitting to you, or to other people, should they be writing a different kind of treatment or are people interested in actually just seeing books?

Ken Atchity: We have a hierarchy of things that we want to see from you. In fact, I give a webinar about that, but the first thing is we want to see a log line, just by itself.

Basically that is the story behind the series. The second thing we want to see, if we like the log line, we're going to ask to see a one pager, and if we liked the one page, or we're going to ask to see a treatment for the series.

And if we liked the treatment, we're going to say, send us one of the books. That's basically the sequence of things that we need.

Joanna Penn: And the log line is something that I think many authors struggle with because, we're used to writing 50,000 words, 100,000 words, and then you want like how many words, 50 words for a log line.

Can you give us a couple of examples of log lines?

Ken Atchity: No, 50 words is more like a one page.

A log line is maybe 10 words, is all we need. What happened? What happens if the husband you adore needs to be a woman? There is a one liner for The Danish Girl.

He was left behind on Mars. There's the one liner for the Martian right.

US soldiers try to save their comrade stationed behind enemy lines. Saving Private Ryan.

Four teenage boys make a pact to lose their virginity by prom night. American Pie.

A log line is the way you would shout it to a friend on the telephone if you only had a minute left and they were trying to decide what movie to see. It’s the simplest and quickest way of talking about a movie.

We had a great project once called The Kill Martin Club, and the one liner was: Advertising mogul Martin Pickford gets murdered a lot. It’s about a group of people who go to a nightclub and fantasize about ways of killing their boss. And, we sold that one to Warner brothers and when you're selling it to a Hollywood, a decision maker or a check writer is that they are, the final decision’s going to come from their boss and the boss is not going to read a screenplay.

He's not going to read the book and he’s maybe not going to read a one pager. They're going to hear the log line. And they're going to immediately say to themselves, I can sell that to the marketing department. And it's the one liner that the marketing department is using to sell the movie.

With The Meg, one of the wonderful ones that we used was, don't even think about going near the water. Another one was, the greatest predator in history is now is no longer history.

So you can see how provocative or one-liner needs to be. And my theory, as somebody who taught classical writing, from the beginning of the times of Quintillion and Aristotle, so going back to them, they called this one liner that we're talking about sententia. That was the Latin word for it. It was called the premise.

And honestly, once you've written the first draft of a novel, there is no way to effectively edit your novel and revise it and make it ready without knowing what the premise of your novel is. If you don't know that premise, then you're not ready to revise because what's going to result is not going to be focused and clear to the reader.

When people say I wrote 40,000 words, but I can't write a one line description of it, I think something's wrong with that picture because that 40,000 words is probably not something that is going to ever work in Hollywood because it's going to take way too much deconstruction to turn it into a movie.

Whereas somebody with a clear premise as a much better chance of selling their story.

Joanna Penn: I think a lot of people will find that difficult because I feel like many writers start with a story and don't come up with a short one liner.

But you're exactly right there. What I want to ask you then, particularly, is the difference between a log line that focuses on character over plot.

In almost every example you gave was focused on character. Even the one with the shark, because in my mind The Meg is not really a character movie. It's a shark movie. It's a monster movie. We don't care about the shark as such. We care about some of those characters, but it's not really that type of movie.

Should we always be focused on character in a log line or plot?

Ken Atchity: The answer is that I don't agree with you that the shark is not a character. It is the character that inspired me. When I first read the manuscript, I saw the description of the Meg and that is what got me to want to represent this project.

And that log line, the greatest predator in history is no longer history is entirely focused on character. I think you have to reshape your thinking a little bit about it because that is the main thrust of a story.

There are examples like The Perfect Storm, for example. The logline is almost the title itself. It’s the coming together of three storms that happened to be hitting the exact place on the compass where the ship is. That is the focus of the movie. But the perfect storm is really the main character of the movie when you think about it.

And so I think it's almost always about character, one way or the other. You need to understand what your main character is doing in order to focus your story.

If you have a series that has 12 main characters and 60 characters, that probably isn't for television or the world of entertainment. It may be an indie. You may raise the money and make it yourself, but, when you think about The Fisher King or Snow Falling on Cedars or American Sniper or Runaway Bride, or Bridge of Spies most of those come down to character.

Joanna Penn: Absolutely. So the tip is that the log line should be character focused because that's where the main conflict is. Even something like Game of Thrones, I guess, which, like you said, mentioned 60 characters. There’s a lot of them in Game of Thrones, but it's still a very character-based logline. I don't actually know what that would be.

I guess Game of Thrones is in itself a log line.

Ken Atchity: Exactly. And think about Psycho or Sleepless in Seattle or one of my favorites, Liar Liar, it’s about an attorney who is forced to tell the truth. That's all about character.

Or maybe another Jim Carrey movie where an ordinary guy suddenly becomes God. It's about that guy.

What we love about stories is, what would happen if a woman like this found her itself in a situation like that. Because if you can't relate to the main character, it's really hard to enlist audiences to spend their time watching that story.

The Horse Whisperer. The greatest movies that we remember are ones about a main character. It may be a massive main character like War and Peace really is about war. War is the main character of Tolstoy's novel. But, most of the time the main character is a person or a horse or a dog. Those are the stories that stick with us the most.

Joanna Penn: Great. So we now have our log line. What do we do with that?

Do we need to find an agent? I've spoken to some people before and the first response has been, why don't you get your literary agent to do this? And I'm like, well, I'm an independent creator, so I don't use a literary agent for my publishing side.

Should we be working with agents or should we be going to festivals? What should we be doing?

Ken Atchity: You should read my book, Sell Your story to Hollywood, and is the subtitle is The Writers' Pocket Guide to the Business of Show Business. It shows you all those things.

But here's the problem. The problem is if you're not here in Hollywood it's relatively dangerous to be pitching one-liners to anyone other than an agent, a representative. I’m a literary manager, so we count too and attorneys, and agents, all three in the same category of literary representative.

They're the safest way for your log line to be pitched because if you pitch it to a studio, first of all, the studios are going to be protecting themselves from getting random one liners. Because they'll refuse your email and then when you get it bounced back to you, it'll even say this email was returned unread because they are not willing to take any kind of liability for a random idea that comes across the threshold. We used to say transom in the world where there were transoms but now that's long gone.

They get so many ideas. Ideas are virtually a dime a dozen. They're probably a dime for a thousand.

What people want is the next step, which is a treatment at the very least. What they really want is a novel, but the catch 22 is getting those novels into the hands of somebody who can read them. And that's where you have a representative who can help do that.

I go to lunch at least once or twice a week and I pitch stories. I always start out with the one liner for the story because if my buyer, whether it's a financer or another producer or a director that I'm pitching to, if my buyer isn't interested in the one liner, I am wasting my breath pitching that story to them. With rare exceptions. So that's how you start.

But you can most successfully do that if you're in the business and you're actually here where you physically have a relationship that's been going on for, in some cases, 30 years. For me, they want to hear the one liners that I give them and then they want to say, what else do you have on it?

I just got an email this morning from a major financer. They loved what I'd sent them, which was basically a one liner. What else do you have to send me? Do you have a script? Do you have this? Do you have that? You see what I mean? So that's, that's why having a representative to Hollywood is important.

We are living in the exciting internet world of getting your own stories out there. And if you're professional and do everything right, then you’ve got an enormous advantage you didn't have 10 years ago when everything had to go through the gatekeepers of the traditional publishers and in London and New York. Fortunately, we've passed by that.

But the problem is that in the old days, 10,000 stories made their way around Hollywood every year, and now it's probably closer to 50,000 or a hundred thousand because a million books are being published every year instead of 50,000 or a hundred thousand that thanks to Amazon and the internet in general. There are so many stories floating around.

It really helps you to have a representative. And one of the secrets I can tell you is that it may be hard to find an agent and hard to find a literary manager, but it isn't nearly as hard to find an attorney. So if you look up in your directories and find an attorney who deals with entertainment, you can actually meet that attorney by phone or in person and get them to represent you and all that will cost you as an hourly fee as opposed to hoping that he'll decide to do it on spec or pro bono.

But I urge people who can't find an agent or a manager to find an attorney, uh, as you know, locally, if they can, but just make sure he has an entertainment experience and credentials.

Joanna Penn: That's fantastic. I've heard that from a lot of people, so that's really good.

I did want to ask you about budgets because I pitched a book to an agent and he said, well, great idea, but that's going to cost over a hundred million dollars. So why don't you write a low budget horror? Because they're easy to get made. I thought that was interesting.

I think I read in one of your books not to think about budget when you're writing a book. What are your thoughts on that?

Ken Atchity: That's a very good question and I understand what the agent told you, but that is based on the assumption that you are desperate to get it produced as opposed to the assumption of going for the gold ring, which is what I usually start out with, for my clients. I want to go for the gold ring.

I'm not the least bit interested in the word low budget because Hollywood doesn't get nearly as excited about that as they do about a hundred million dollar plus budget. That gets people's attention more than anything else.

Money is not an issue. It's always how good is this story and how powerful are the roles of the protagonists and antagonists, and are they powerful enough to attract stars? Because that's what makes the big movie work.

So I would say it all depends on what your goals are. If your goal is to go for the moon, then I'd say write the high budget story.

If it's just to get produced, because you think somehow that's going to make their lives better, which it possibly will, then take the advice and write a little budget story.

But I really hate to see writers guessing about budgets because, for example, writing a low budget story that takes place in the middle ages is not going to be a low budget movie, even if there are only a few characters and this and that.

I think the purpose of writing and the function of writers is vision and sharing their vision with the rest of us, and I really hate to see them trimming their own vision with financial sheers that they aren't necessarily going to be too good at doing.

Joanna Penn: And at the end of the day, you've got to write what you love. And I love big action adventure movies. I love big Hollywood and explosions and blowing up the Eiffel tower. That's what I love to watch. So I'm always going to write books like that, which are big books.

People who love small, literary, one room books. There was a movie about that. Wasn't there a movie called Room? I think there was. And that's possible, but you've got to love that kind of writing.

Ken Atchity: You have to love it. That's true. So hopefully you won't be writing anything you don't love.

Joanna Penn: Life's too short. Absolutely.

I did also want to ask you, because I noticed that you've also written, obviously you've written some nonfiction books, which you've mentioned, but you've also written The Messiah Matrix, which attracted me because your blurb says, ‘For fans of Dan Brown and James Rollins’, which is absolutely my target market.

These books seem to be cross genre. So I wanted to ask you about cross-genre because many people find books harder to sell when they fit between genres and are not quite clear.

What are your thoughts on these cross-genre niches, and should we be aiming for that or should we be really aiming for very clear genre?

Ken Atchity: Again, that is a, you know, that is a logical question based on the very opposite of what the creative world is based on. The creative world is based on thinking outside the box. And that is a question that is created by the box makers. And the box makers always love you to be focused on a genre.

They don't like cross-genre because frankly they don't know where to put it in the bookstore. But fortunately, bookstores are not determining the future any longer. The internet is much less boxy than bookstores are. So I don't really think that way.

If I’ve got a book in front of me, which I do often, that is both a thriller and a romance, I'm going to make a decision of how to pitch that depending on who I'm talking to. And at the end of the day, if it gets made into a movie, it will probably be marketed as a thriller, for example, or as a romance, not as a cross-genre thing.

Cross-genre is not a word that anybody really uses in the real world other than marketers. It's not a creative world.

In your ARKANE series, for example, which is similar to The Messiah Matrix in some ways, I just see these as primarily thrillers. How do you see them?

Joanna Penn: I see them as thrillers too. But I feel like I'm much of that kind of Dan Brown… at one point they might have been called religious thrillers, but they're not Christian thrillers, so they kind of fall down a gap. But I agree with you. I think it's just thriller.

Ken Atchity: Yeah. And that's not really cross-genre. Cross-genre is when you have a sci-fi romance, for example.

I'm having trouble selling a book right now that is a story about going back in time to save the life of a woman the guy's in love with. I love the romantic part of the story more than I do the sci-fi part of the story and unfortunately when I send it out through traditional publishers, they're seeing it as sci-fi and they're not feeling the romance comes through as strongly because it was subordinated to the other genre.

It's very hard to find a traditional market for a story like that. But if you made it into a movie and focused it on being a thriller you wouldn't have a problem. People going out to watch the movie will not stop at the pub after the movie and say, well, it was kind of cross-genre. Nobody would say things like that, who loved the movie.

That's only something that marketing gurus say, and people who put things in pigeonholes say.

Joanna Penn: And I guess now, as independent authors and publishers, we have to put things in pigeonholes because we have to do the publishing. But I like the idea that we can break out of that.

We're almost out of time. I went on your websites. You've got lots of websites and lots of books and lots of information for people to find out more.

What is the best place for people to come to you and what would they find in terms of what you do?

Ken Atchity: It took me a while to figure all this out because I realized over the years that I've been basically creating companies to respond to needs that I saw in the writing community. I've been working with writers my whole life, and so I have one company that is an editorial company and writes books for authors who really don't want to write. They just have an idea. That's my oldest company, The Writers Lifeline.

And I have other companies that represent writers to traditional publishers. And I have company that publishes writers who don't make it with traditional publishers, but I still need them to be books so I can sell them to Hollywood.

And then I have a couple of production companies, but all of it is brought together in a website called storymerchant.com where on that landing page you can see what the different companies do, and which one might be best for you. And also see videos that I've done and interviews and books and so on.

So storymerchant.com is the one stop place to meet me and what we're up to. And it even has a place where you can tell us about your story, as an email basically right there on the site. So that I hope answers your questions and I'm always happy to talk to writers and to, one of my greatest joys as a professor was helping writers.

Unfortunately as a manager, I get to help one writer, but I actually don't spend as much time as I would like to talking to writers. And that's why I do podcasts and webinars to try to teach them that way. Thanks to the internet and making it possible for all of us.

Joanna Penn: This has been fantastic, and I know you've given everyone lots to think about, so thanks so much for your time, Ken. That was great.

Ken Atchity: Well, thank you, Joanna. I really appreciate it.

I believe that not all the films that were shot on the plots of books are successful. As an example – the book “Basic Instinct” (the fact that the first came to mind). It is not interesting to read such books, the feeling that you are reading a script, it seems to me, is no dynamics. In general, any book is more interesting than a film, because no filmmaker, not a single director of tricks can compare with the imagination of the reader. You watch the movie after the book you read, and everything is not there as you imagined… Although there are exceptions and the film is much more interesting than a book, it is rare.

This is actionable insight from an expert in the Hollywood end of the creative pool. Thanks for sharing it!